|

Christchurch and District Model Flying Club |

|

BEFORE I FORGET BY KEN SPOKES Part 3, continued from the September 2018 Sloping Off |

Like many of my friends, I joined the local Air Training Corps where we were instructed in subjects such as basic navigation, meteorology, the morse code and aircraft recognition in preparation for the time when we would be called up to join the RAF. This all took place several nights a week but at weekends, visits were arranged to aircraft factories and RAF stations where, if you were lucky, you might get a flight. Cranage was our nearest airfield where during the Blitz, night fighter Defiants had been based but was now home to a fleet of Avro Ansons

used for navigation training. It was in one of these that I had my first ever flight.which was local and lasted about half an hour. During the course of the war, I was fortunate to have flown in a number of different service aircraft including an Oxford, Havard, Dominie, Walrus, DC3, and a Tiger Moth. No Health and Safety in those days as were never issued with parachutes and in the larger aircraft, were not strapped in and were often able to wander around as we pleased On several occasions I stood behind the pilot and co- pilot on the landing approach.

Once a year we attended a week’s Summer camp ( I’m back row right) where we had an opportunity to observe all the day to day activities at an operational RAF airfield..The highlight was a flight in whatever aircraft was available. One such visit was to RAF Thornaby where Vickers Warwicks were used for anti-submarine and airsea rescue missions It was there that I had a flight in a Walrus which turned out to be not particularly enjoyable as four of us were squashed in the small cabin and most of the flight took place at about fifty feet over the sea.

With the war over, gliding was an added weekend activity for ATC members. Barrage balloons were no longer needed so the glut of winches were put to good use to launch gliders. Sundays were now spent at Cranage airfield learning` to fly a single seat Slingsby Cadet. When not actively flying , we were kept busy operating the winch, retrieving gliders and repairing those that had been damaged - full scale aeromodelling which I thoroughly enjoyed. I progressed through ground slides, low and high hops but before facing the ultimate challenge of a full circuit, the Gliding School closed and moved to Woodvale in Lancashire - unfortunately, too far to travel to continue which sadly ended my short career as a glider pilot.

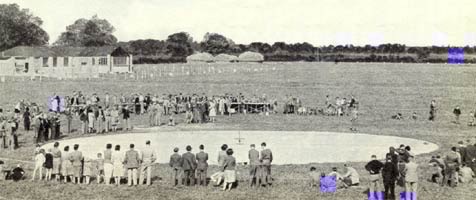

Many years later, I took to the skies again as a passenger in a glider at Lasham when on that occasion, the launch was an aero-tow It was a dull day with no thermal activity so we just did a couple of circuits and landed About this time, someone in the Aeromodeller office had the bright idea that what was needed was a venue wholly dedicated to aeromodelling where enthusiasts could visit to fly their models and where major competitions could be held, A site was procured at a place called Eton Bray in Bedfordshire and facilities such as toilets. restaurant and a shop were planned.It seemed popular and from what we read in the press, the place was where it was all happening in the model world. A friend and I decided that a visit was a must so we set out early one morning to take the steam train to Layton Buzzard , a journey of over three hours. Then by bus to Eton Bray.

When we arrived, there seemed very little activity but eventually we spotted a small group of people standing around a petrol engined model. We wandered over to find the owner crouched down flicking the propellor attempting to get the engine started. We hung around expecting it to burst into song at any moment but no joy. No other model flying took place. The field was much smaller than expected with a concrete circle in the centre for tethered car racing and a few sorry looking buildings near the entrance gate. The weather up to this point was overcast and dry but now we felt a few spots of rain and decided that nothing was to be gained by hanging around and that we would make our way home That the visit had been a washout was nothing compared to the journey back to Layton Buzzard, The rain quickly turned into a deluge and after waiting for a bus that never came we decided to walk back to the station where we eventually arrived soaked to the skin. Later the venture closed down due to planning and financial problems. .Also about this time I travelled to London for a day visit to an early model exhibition held at Dorland Hall. Four hours each way! I must have been keen - or mad. All I can remember is that it was extremely hot and crowded and watching a demonstration of electric “round the pole” flying which was then a new feature of the hobby. Shortly after the war ended, my Call-up papers arrived for National Service. Having been in the ATC ,I fully expected to join the RAF but to my dismay, was instructed to report to Wrexham to carry out basic training with the Welch Fusiliers Dreams of the wild blue yonder terminally dashed! Fortunately, I was saved from spending the remainder of my National Service in the Infantry since having worked for the GPO Engineering Department, someone must have thought that I could be more usefully employed in the REME and consequently, was posted to a small unit based in Totton near Southampton. It turned out that this was a depot for servicing American built mobile radar units which no one seemed to know anything about - trained personnel having long since been demobbed. It was a case of the blind leading the blind but I found the microwave technology fascinating and far removed from telephone systems. However my time there was short lived when to my surprise I was informed one day that I had been selected for officer training. This took place at Eaton Hall near Chester and was a truly mind blowing experience. The course lasted several months during which time I have never before or since been so tired, so shouted at, and at times, so miserable in my whole life. (I know, I know - Ed) Not surprising, some gave up and were returned to their units, but I struggled on and managed to complete when I was informed that I would now be transferred to the Royal Signals at Catterick

and that I would have to endure a further six months training before finally being commissioned. Not something to look forward to. Fortunately, in comparison to Eaton Hall, life was relatively relaxed and was confined mostly to classroom and field exercises with the emphasis on radio theory and practice. The only “fly in the ointment” was that the CO was a bit of a sadist who organised regular boxing bouts

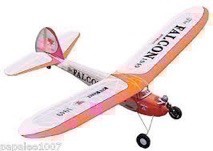

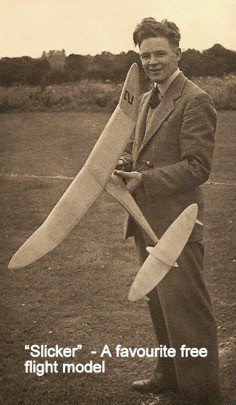

when for three round we were expected to knock “seven bells” out of each other. He called it character building. but I can honestly say it did’t do anything much for my character. When our final postings were announced, I was assigned to a Training Regiment at Signals HQ, Catterick. which was disappointing as I had hoped to be sent abroad and see a bit of the world. In the event, it turned out for the best.. The HQ mess was five star and the duties less than onerous.. I had the opportunity to "play" with the then state of the art signals equipment and to set up a museum of captured German, Italian and Japanese communication equipment.. I had time to do a bit of modelling and often flew a Slicker free flight on the Regimental golf course in the evenings.This was powered by a Frog 100 diesel which for some unexplained reason , would only run inverted. I enjoyed the life so much that I gave serious thought to joining the regular army. However, I had by this time become quite friendly with the garrison Education Officer who mentioned that on his demob , he was going to University with a grant, as his education had been disrupted by his call-up. I had similarly been in the middle of an ONC/HNC night class course and with his help, found that I was also entitled to a grant for full time education to complete what I had started. This was too good an opportunity to miss and the next two years were spent at St Helens College studying Electrical engineering and at the Borough Polytechnic in London studying radio and TV engineering which on completion qualified me for graduate membership of the IEE and the IERE. During this period there was no time for modelling although while in London I did manage an afternoon visit to Fairlop This was a popular venue for North London modellers and while there, I saw my first radio controlled model.

This was a large KK Falcon high wing cabin model which made several stately circuits of the airfield under full control. I came away most impressed. Following my studies, I returned to the Post Office and within a year or so was promoted to Assistant Engineer and transferred to the Engineer in Chief's office, in London… In the late 40s, Farnborough began hosting an annual airshow.. My first visit was in 1952 and as events turned out, was almost my last. Two of the major attractions that year were Nevil Duke flying the latest RAF fighter, the Hawker Hunter

and John Derry in the De Havilland 110.

Flying faster than sound was very much in the news at the time and there was some excitement as we waited to hear the sonic boom when the Hunter broke the sound barrier. I was watching the display from a bank about half way along the runway and had an excellent view of the flying. I remember the DH110 taking off and after a few minutes make a high speed pass at low altitude from left to right with flashes of condensation appearing along the wings. The plane then turned to port and sweeping around came at 90 degrees back towards the runway when,suddenly, it broke- up in mid-air. The full horror of the event was not apparent until a few moments later when two distant specks rapidly grew into two jet engines coming straight towards us. Everyone ducked as one sailed low overhead and crashed into a hanger while the other landed in the crowd immediately to my right killing nearly thirty people and injuring many more. All flying stopped for a while but I had suddenly lost interest in air displays and along with many others, decided to leave very thankful to be in one piece.

Post War, the modelling scene changed out of all recognition The diesel engine made its appearance with makes such as Mills, ED and Frog being popular and affordable.The first engine I owned was a Mills 1.3 Mk1 which initially,I had difficulty getting to run.

It turned out that the problem was the fuel, which at that time was not commercially available,so it was very much a case of brewing your own..This involved a great deal of experimenting using ingredients such as petrol, paraffin, castor oil, lighter fuel and ether, Eye of newt and toe of frog - hadn’t a clue what I was doing but eventually it turned out that I had been using commercial ether in the mix and when this was changed to the more volatile surgical grade it was a first flick start almost every time. The balance between compression and throttle setting for maximum performance was quickly learned.For many of us, free flight rubber powered models were now replaced by 50 - 60" span free flight diesel powered " monsters " and a whole new era of aeromodelling was ushered in..No longer the gentle silent flight of featherlight and flimsy creations. Models were now noisy, smelly, oily and much more robust. Also much more fun.Trimming was speculative and the first flight most nerve wracking wondering if the desired climb, gentle turn and stable glide after the motor cut, would be achieved Sometimes it was just the opposite with a quick climb, a fast turn and a full power crash and back to the building board. Other times, it was a chase for a "Flyaway" and a hunt to find where it had landed. With experience, many models were built with excellent performance with names such as Bandit, Banshee, Outlaw and Slicker. Of these, the Slicker was probably my favourite.

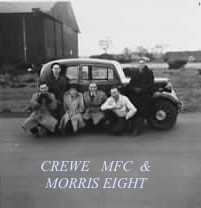

“Bitzers” proliferated made out of the many surviving leftovers of crashed models. Control line flying was very popular. I tried it with a couple of models, but somehow it never appealed. Turning round and round made me dizzy and on one occasion I fell over and let go of the control line handle. I expected the model to crash but to my amazement and to those watching, it started to climb in tight circles trailing the wires and handle below it. Having gained a considerable height, it ran out of fuel and just tumbled out of the sky.About this time, a model club was formed in Crewe, and joining, I was surprised to see the high standard of construction some of the models members were flying.

Until that time, I had been quite happy with my efforts , but clearly, there was much room for improvement. One member in particular was a superb craftsman. He was about my age and we soon became good friends . His meticulous approach to work began to rub off in my model-making and I found I was striving to reach his standards. I don’t think I ever did but there was no doubt that under his influence, my models were now very much better built The Goode brothers in America and others had proved the feasibility of R/C with many successful flights and as articles began to appear in the Aeromodeller giving circuit and building details for simple transmitters and receivers, I decided to try my hand and build my own system.

There was no shortage of components since the post war surplus stores were awash with all manner of receivers, radar sets etc. that could be bought for a song and broken apart. Most however,were in full working order and at one time I had an American BC348, an RAF1155

and a Hallicrafter all set up at my bedside for nighttime listening to anything that I could pick up on the short-wave bands. It was interesting eavesdropping on the amateur radio transmissions The rear of the house was festooned with a weird and wonderful array of aerials in an effort to improve reception. Also, working in the Post Office Auto Exchange at the time I was able to scrounge many useful bits and pieces from the scrap bins. Old relays were a wonderful source of enamelled wire in all gauges for making actuator electro-magnets A 27Mhz band was allocated for radio control and transmitters simply sent out an unmodulated signal on that frequency. As such, there were no designated channels - not that it would have mattered,as at that time you could almost have guaranteed to be the only one flying R/C. The transmitter presented few problems. The circuit was very simple, but being valve operated , required a “high tension” battery of anything up to 120 volts and a 2 volt lead acid battery to heat the valve filaments. As can be imagined, it was a hefty bit of kit which was normally placed on the ground. It had a large vertical whip aerial and a cable with a hand held on/off press button switch. The receivers were a different matter.. The very early designs I used were known as Superregenerative receivers, which used a single thyratron valve.

In simple terms, when receiving no signal this receiver passed a current of about 2.5 milliamps through a sensitive relay whose contacts remained open..When a signal was received the current dropped to nearly zero causing the relay contacts to close. So, by switching the ground based transmitter on and off via the hand held switch, contacts in the receiver would open and close in sympathy. To provide the necessary movement of the rudder, a rubber powered four point actuator was used which was connected to the receiver relay contacts via a 1.5v dry battery. This was a home-made device which at the time, turned out to be about the most reliable item in the model. Since only functional drawings were available, its construction was a process of trial and error until a satisfactory design was achieved.. Much later in the 50s these became commercially available from a firm called Elmic. With this setup, flying - or perhaps I should say steering a model - was really quite simple First the receiver was switched on then by pressing the transmitter switch "on" and holding, the rudder would flip a set amount in one direction. Releasing the transmitter switch ie, turning the transmitter "off" would return the rudder to neutral. The second press of the transmitter switch would flip the rudder in the opposite direction. It really worked very well - at least once you had got used to the switching sequence. More complicated actuators were made with delayed sequencing in an effort to provide elevator and speed control of the diesels. When playing about with the fuel mix, I had noticed that a higher ratio of castor oil caused the motor to run slower. The idea was that a two mix fuel supply would feed the engine - one for fast running ,the other for slow and that a second actuator, quick blipped within the delay of the first, would cause a valve to switch between the two. Unfortunately, the diesel didn’t respond well to the dual fuel mix which required different throttle and compression settings for each mix.. Ah well, you can’t win them all. It was amusing to find that with extreme castor oil “doping”, a motor could be made to run so slowly that it could easily be hand held while popping away.

I found the receiver most difficult to adjust..

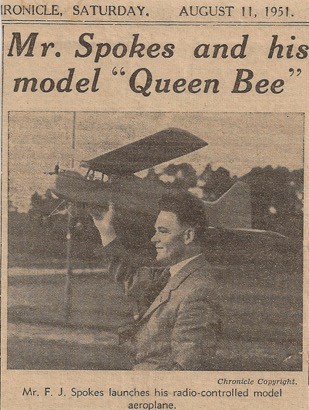

It had relatively few components but small changes in values would have quite a significant impact on performance. In an effort to get maximum range I hit on a cunning plan. I built a pulser that switched the transmitter on and off at about once per second and mounted the receiver and batteries in my daughter's pram and off we would go down the road, baby and all. With a milliameter ( an AVO Minor which I still have today ) in the relay circuit I would watch the needle pulsing until it stopped ,maximum range having been reached. Then back home to more tweaking and repeating the process. All very trial and error without access to a scope or worthwhile test equipment but in the end, I managed to make a system that worked with a reasonable range. I was given some UHF "Acorn" valves and built a transmitter and receiver in that band but after spending a lot of time and effort, I have to admit that I could never get it to work. Over the years , there have been several attempts to market such systems in that frequency band but not until very recently has there been any real success. Radio control meant that models could now be flown in much smaller spaces such as local parks and playing fields resulting in less traveling and more flying time.. Flights could be made in windier conditions and “fly-aways” avoided.(assuming the radio system didn’t fail) Unfortunately, the downside was that models droned around the sky for much longer and noise pollution started to become a problem. Much time and effort was spent making and fitting silencers. By the mid 50s,the simple receivers were replaced by more reliable multi-valve circuits. At this time, commercial equipment also began to appear in the form of kits and complete systems. The first R/C model I ever flew was a Bill Winter "Citizenship" This was a high wing cabin model with a wingspan of about 60" and powered - underpowered would be a better description - by a Mills 1.3 to be later replaced by the 2.4 version. The receiver was built on a small square of paxoline suspended in the cabin by a rubber band at each corner. This effectively damped vibration which could cause the highly sensitive relay to “chatter” The rubber powered rudder actuator was mounted near the tail. The heavy high voltage,, low voltage and actuator batteries were wrapped in foam at the CG. On/Off battery switches were made out of safety pins - light and cheap.There was no throttle control which was typical of all the early diesels. Prior to its very first R/C flight,I had test flown the model free flight with a payload equivalent to the R/C gear - it flew, but was very sluggish.. Bearing this in mind, the problem was how much rudder deflection I should set and what would happen when it was applied. Would it spin in and if so could it be recovered with opposite rudder? On a nice calm day on a disused airfield the model was hand launched and with the Mills on full song it climbed slowly away .With some height gained and my heart in my mouth, I pressed the transmitter button. For a moment , nothing happened then slowly it went into a gentle turn to the left with little loss of height. Another press of the button and it straightened up and flew overhead. Absolutely fantastic - I just couldn't believe it was happening. A few more controlled turns and the motor cut . More by good luck than judgement, it was pointing towards me and glided in to land not more the twenty or thirty yards away. It's hard to believe that anyone could get so excited by an event like this but having since flown scores of models for hundreds of flights I can honestly say that this is the one that gave me the greatest thrill and the one that will always be remembered. Shortly afterwards, a reporter from the local paper thought the event was worth a few words (and a posed photograph.)

Next time - bigger and better models, cars, career moves...all in the March 2019 Sloping Off |

|

[Home] [Chairman's Chatter] [Ken's] [Flight Sim] [Aerotow] [Aerotow 2] [Full House] [Hurricane] [Indoors] [The Hoov] [Tailpiece] |